|

AUSTIN, Texas- A program at the Steve Hicks School of Social Work’s Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing has received a $10,000 grant from the Texas Bar Foundation to provide targeted training and support to legal professionals working with immigrants, asylum seekers, and refugees.

Since 2018, Girasol Texas has worked to support the wellbeing of immigrant families and those who serve them across Texas and nationwide. This new funding will allow Girasol to implement a Training and Consultation program designed to lessen the impact of vicarious trauma and promote positive mental health for legal professionals working with immigrant populations. “Thousands of migrants enter Texas each year seeking asylum, and the legal community in our state has been on the frontlines providing necessary services for them,” Girasol Senior Program Coordinator Monica Romo said. “Because migrants typically experience trauma before and during their journeys, legal staff must absorb highly traumatic stories of violence and struggle with grief and burnout. Our Training and Consultation program will fill a critical gap to help legal professionals process their vicarious trauma.” Over the next year, the funding will help Girasol offer free virtual and in-person training sessions to organizations and private attorneys providing pro bono services in the immigration field. Training will include workshops focused on topics including coping with vicarious trauma, as well as psychosocial support groups aiming to build mutual support among legal professionals. “Our work with legal professionals allows us to not only encourage self-care and resilience-building, but also to create systems that provide the support legal professionals need to serve their clients without sacrificing their own mental health and wellbeing,” TXICFW Director Monica Faulkner said. This marks the second year Girasol has received this critical funding. In 2022, the Texas Bar Foundation awarded the program $10,020 to fund an expansion of its Mental Health Collaborative, a project that trains qualified mental health professionals to support immigration cases. Since its inception in 1965, the Texas Bar Foundation has awarded more than $25 million in grants to law-related programs. Supported by members of the State Bar of Texas, the Texas Bar Foundation is the nation's largest charitably-funded bar foundation. CONTACT INFORMATION Kate McKerlie Communications Director Girasol Texas | Texas Institute for Child and Family Wellbeing Steve Hicks School of Social Work | The University of Texas at Austin [email protected] (512) 232-0648 Girasol is seeking a new fully remote Program Coordinator! This grant-funded position will be responsible for coordinating the Girasol program projects to support the mental health and well-being of immigrant youth and families via training, coordination, and resources for professionals.

Responsibilities will include:

Learn more and apply today! At Girasol Texas, we’re building a network of trauma-informed professionals to support the health and wellbeing of all immigrants. Our team, housed at the Texas Institute for Child and Family Wellbeing, trains students and professionals statewide to meet the needs of immigrant families.

In 2019, we launched the Mental Health Collaborative to help immigrants seeking asylum in Austin. Nearly all of our immigrant clients report fleeing their home countries after experiencing violence—ranging from threats of homicide to persecution based on their politics, religion, or race. The Collaborative trains qualified mental health professionals to strengthen the cases by validating the impacts of persecution. Our team also coordinates cases for immigration attorneys whose clients can’t access mental health services. The Collaborative has trained more than 100 mental health professionals and students and created a database of licensed mental health evaluators with the support of our partners RAICES, American Gateways, and the Texas Bar Foundation. Over the past five years, the Collaborative coordinated assessments for 70 cases involving immigrants seeking asylum and other forms of legal protection against deportation. “We created the Mental Health Collaborative as a way to build a connected network of professionals supporting immigrants,” said Ana Vidina Hernández, Girasol’s Program Coordinator. “Our clients rely on these services to help demonstrate the emotional and psychological harm they’ve experienced and present persuasive cases to avoid deportation.” Navigating the Asylum ProcessThe process of navigating the U.S. immigration system is overwhelming on purpose. In the U.S., individuals seeking asylum must express a fear of returning to their home country to avoid deportation. They then must prove that fear through an interview with an asylum officer and a presentation of their case before an immigration judge. If asylum seekers don’t have a good translator or don’t understand the questions being asked of them, there’s a strong chance they won’t pass. And for those who do, most have to represent themselves before the judge—because immigration court does not guarantee the right to an attorney. Most asylum seekers without legal representation are denied, while nearly half of those with representation are successful in their application. “Imagine having to stand in front of an ICE officer and having to tell them the most horrible things that have ever happened to you—things like sexual violence, that are rooted in shame,” said Dr. Monica Faulkner, director of the Texas Institute on Child and Family Wellbeing. “People who have never spoken about or processed the violence they experienced are now asked to explain what they have experienced to a stranger who decides their fate. It’s completely understandable why people struggle with this process and why mental health professionals can play a role in helping.” Girasol’s Mental Health Collaborative strengthens asylum cases by training mental health professionals to conduct mental health evaluations. Our trainings also teach professionals how to write testimonial letters to judges speaking to the fear and trauma experienced by clients. For most of the cases coordinated through the Mental Health Collaborative, the professional working on the case evaluated the client and wrote a letter discussing symptoms, trauma history, and their professional recommendation to the judge. “We’ve created a system for coordinating and training folks on how to write letters of support for immigration relief cases, and we’ve worked hard to provide a stipend for trained Collaborative members to compensate them for their time,” Ana said. “These services are vital for helping both attorneys and clients present their cases.” Up until last year, these mental health assessments took place in the Austin community or detention center settings. That, like every other aspect of daily life, shifted drastically for the Girasol team last spring. COVID-19’s Impact on the Collaborative When the March 2020 Stay-At-Home order took effect in Austin, detention centers closed their doors to outside visitors. “April 2020 was an interesting moment for our organization,” Ana said. “We’d just figured out the process of getting folks together to write assessment letters for detention cases. That typically meant we had to drive four hours out to a detention center with the hope that we could see our client.” From there, mental health professionals would have to set aside another two to eight hours to conduct the mental health evaluations that informed their assessments. For Girasol, the Stay-At-Home orders meant they had to get creative to advocate for immigrants in detention. “The shutdown made it harder to get to people but easier to conduct remote evaluations,” Ana shared. “Because providers were forced to go virtual, all of a sudden there was an evaluation system for us to use that opened up all different types of accessibility. We could help more people in more places because we could reach them by phone. We no longer had to drive for hours to talk to our clients.” The pandemic offered a new opportunity for extending the reach of the Mental Health Collaborative. Over the past two years, Girasol has hosted regular online workshops and trainings for professionals. Mental health evaluators in the network benefit from free one-on-one and group consultation sessions with Girasol experts. The Girasol team also created a trauma-informed workbook to help women in detention. As the Collaborative expands throughout the pandemic, the Girasol team has kept its focus on building a supportive network for both clients and professionals. “We really want our Collaborative members and prospective volunteers to know that they’re not alone in their work, and we will support them at every step in the process,” Ana said. “Regardless of the outcome in the courtroom, the family you advocate for with your words can tell their story. That is something we’re proud of.” To learn more about joining the Mental Health Collaborative, visit our webpage. AUSTIN, Texas- For individuals navigating the U.S. immigration legal system, there is a major gap in accessible services. Many immigrants are survivors of violence serious enough to flee their home countries and experience mental health impacts from trauma. In most cases, their mental health and trauma histories are not adequately evaluated, considered, or represented in the immigration documentation process.Girasol Texas, a program at the Steve Hicks School of Social Work's Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing, aims to change this systemic gap through the Mental Health Collaborative, a project that trains qualified mental health professionals to use their clinical skills in a new way—to evaluate individuals seeking legal immigration relief and write a letter of support for their case.

This past April, the Texas Bar Foundation awarded Girasol Texas $10,020, to fund an expansion of the Mental Health Collaborative. Since its inception in 1965, the Texas Bar Foundation has awarded more than $22 million in grants to law-related programs. Supported by members of the State Bar of Texas, the Texas Bar Foundation is the nation's largest charitably-funded bar foundation. The Texas Bar Foundation grant will fund a new partnership with local immigrant-service organization American Gateways. Through this partnership, the Mental Health Collaborative will coordinate evaluations and letters of support for 15 American Gateways clients whose cases would benefit from their services. Girasol Texas will focus on expanding, evaluating, and improving their program methods. The goal is a coordination system that is effective, replicable at different organizations, and scalable to serve more clients. When a person is in the midst of a violence, they are rarely positioned to collect the evidence that courts look for in their decision to grant documentation. These missing pieces can negatively impact the outcome of immigration cases. Survivors of violence may be denied asylum or left waiting in a detention center for years. “Therapists can be trained to help assess and explain mental health challenges and trauma. This can become a critical piece of evidence that helps the courts understand what an immigrant has been through,” founder and program coordinator of Girasol Texas Ana Hernández said. Mental health evaluators can make critical contributions to legal cases, but because there is no coordinated systems-level approach to integrating legal and mental health services, it is often costly and inaccessible for immigrants to have a mental health evaluator work on their case. Since it started in 2019, Girasol has trained over one hundred mental health professionals in Texas and began coordinating the first 40 cases. Although the results of immigration cases can be difficult to track, Girasol’s preliminary data shows that the Mental Health Collaborative’s model can successfully aid legal teams in obtaining legal relief for clients. In a case this year, a woman who fled persecution and abuse in Angola and then faced further oppression during migration, was detained in the United States. After Girasol coordinated the evaluation and letter of support, she was released from detention and connected with a local community-based shelter. The letter this woman received from the Mental Health Collaborative can also strengthen her future asylum case. Hernández says that Girasol’s virtual trainings have begun drawing mental health professionals from around the country. Eventually, Hernández would like to expand the Mental Health Collaborative into a nationwide initiative—a network of professionals around the United States who prioritize the wellbeing of immigrant communities. CONTACT INFORMATION Kate McKerlie Communications Director Girasol Texas | Texas Institute for Child and Family Wellbeing Steve Hicks School of Social Work | The University of Texas at Austin [email protected] (512)-232-0648 Girasol was launched in September of 2018 as a culmination of over two years of volunteer work with immigrants in detention and training for the professionals who serve them. In this two year report, you'll learn more about what we have accomplished and what is on the horizon as we continue to work at the intersection of immigration and mental health.

Reflections from the Border: Experiencing the Effects of Recent Immigration Policies in July 201910/23/2019

In early spring of this year, there were vague whispers of border policies shifting once again. By the time our Girasol team went south in July, the border experience that they had previously witnessed had changed dramatically. This was the third border trip that Girasol has taken within the year. Scheduled every season, these dedicated social workers and students get the chance to assist in firsthand support for immigrants who have just been released from detention. This summer, 13 students and social workers traveled to three border towns in three days: McAllen, Brownsville, and Harlingen. As we gear up for our fourth and final border trip of the year (which will be in early December), here are some reflections from several of our border trip members from July, and the changes they saw from the first two border trips to now. Special thanks to Central Texas MoveOn for their July border trip donations, courtesy of our Girasol Amazon Wishlist. In July 2019, 13 Girasol social workers and students went to the Texas Mexico border to aid immigrants released from detention. What one word or phrase sums up your experience? Monica: Exhausting Nataly: Encouraging Jim: Overwhelming Ana: Complex In what ways did you see the practical impacts of recent immigration policies we’ve been reading about in action during the border trip?Monica: It was amazing to see “the list” and the people waiting on the other side of the border. It was also interesting to see so many migrants from Venezuela this time. Nataly: We saw variety in the composition of families, but never the full family with both parents. Some of the people we spoke to at the bus station had a family member in detention or had been separated from their children. Both expressed fear of never seeing their family members again. It seems that McAllen has collaborated with Catholic Charities, so in that city there is an informal system of getting people to community-based services. But this means the community is having to pick up the slack and do the hard work. Because of the backlog in immigration proceedings and lack of resources from the government to adequately manage this situation, most of the migrants did not have a date for their immigration hearing. If I understand correctly, when their names are called to be let into the US, they are then placed in detention. Imprisoned. That is how immigrants spend their first few days in the US. Jim: After all the recent headlines and news coverage concerning overcrowding in detention centers and their poor sanitary conditions, it was impactful to witness the restorative dignity families received at the Catholic Charities Respite Center through something as simple as a clean shower, a change of clothes, and a place to sleep. It was also difficult to witness so many sick children, to imagine the stress and trauma they have endured through their journey and recent detention, what illnesses might be spreading through the current lack of sanitary conditions in those detention centers, and the potential long-term impacts of childhood illness spread through these poor sanitary conditions. My job as volunteer was to clean the respite center’s sleeping mats with a solution of soap, water, and bleach. I found myself reflecting on the power and importance of cleanliness and dignity. With each mat I cleaned, I imagined who might be sleeping there, and wished them a good night’s rest and good health in their journey ahead. Ana: There was a big difference in what we saw on the physical border and at the migrant shelter compared to the past two trips. The “Remain in Mexico” policy was clearly impacting the numbers of folks making it across the border, as we saw about a third of the number of families at the shelter. While this made the environment less hectic, we also heard about the shelter talking through getting supplies to similar programs in Mexico who were now taking in more people. Hearing about threats against migrants waiting in Mexico definitely made me concerned for their safety and caused me to contemplate the gravity of policies that we hear about on the news. Social workers and students walking to the border. What did you find most useful to support your self-care during the trip and what supports did you seek after coming back from the trip? Jim: The experiences were at times overwhelming and taxing both physically and emotionally on my body and mind. As a non-native Spanish speaker, I found my language faculty at times diminished under the stress of the trip. Maintaining my own self-care, and turning to my peers for support where I needed it, allowed me to re-access my Spanish-language abilities and connect with families at the respite center and bus station. These connections, both with my peers and with immigrant families, continued to help strengthen my personal sense of self, confidence, and well-being. Ana: I found myself tracking my energy levels and need to take breaks, particularly while cleaning the enormous pile of mats. I also appreciated processing the experience with others on the trip to feel supported and connected. I also took time each evening to re-center and re-ground myself through some of my bed-time rituals that help me to release stress. I think it can be hard to engage in these when we spend all day seeing the circumstances of folks waiting at or recently having crossed the border. I find it important to invite self-compassion and know that it takes energy to do this work, so it is always important to re-charge. MSSW Graduate Student and Girasol volunteer Jim Rowell handing out supplies near the border. If you have been on a previous border trip, what stood out to you as different this time around?

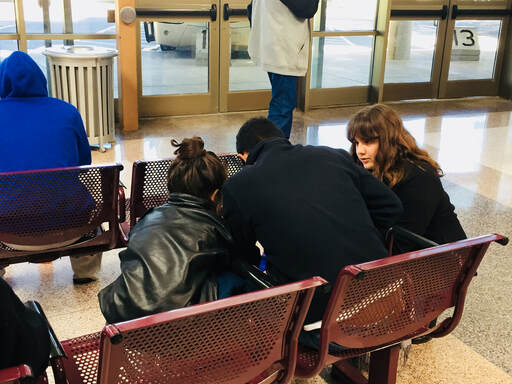

Monica: The cries of the younger children stay with me. As a mom, I can tell a hungry or tired cry. But these were cries of emotional pain that I had not heard. When these children are in the hielera (holding cells) with their parents, even if they are not separated, attachments are disrupted. Children look to adults for protection. When their parents cannot feed them when they are hungry or help when they are sick, the parent/child relationship changes. Ironically, that parent who traveled thousands of miles to save her child’s life, now has a child who is angry with her when it is the fault of every American that we lack a true humanitarian response to a humanitarian crisis. Ana: I found that this time, volunteers were more triggered and affected by the situations of children everywhere we volunteered. This made me consider all of the ways we can work to stay regulated and grounded individually and as a group. It is always hard to witness suffering, particularly when we feel as if we have little control over both the larger system and the individual we are supporting. As social workers, it involves never-ending work of self-reflection, self-awareness, and learning/implementing what helps us feel regulated. I was so inspired by how our volunteers continued to bring caring, compassion, and energy throughout the weekend as they worked to navigate those challenges. Girasol’s Social Work Detention Response Team at the U.S./Mexico border in March 2019 “Heavy, yet hopeful.” “Emotionally challenging but utterly gratifying.” “Chaos and desperation combined with warmth and strength.” This is how it feels today when you go to the U.S./Mexico border. In March of 2019, TXICFW’s Girasol team took a total of eight social work student volunteers to the U.S./Mexico border. This multi-lingual, dedicated team drove 10+ hours over a single weekend to provide relief and support in the border town of McAllen, TX. While the trip was brief, their scope was large: Girasol volunteers worked to support a humanitarian respite center that receives 300-400 migrants each day. In addition to providing directions, supplies, services, and general support, Girasol also helped staff a bus station to provide migrants with access to information about their trips and their initial court appearances. This summer, we are working hard to grow our social workers response team to twelve student volunteers by raising money for these trips through UT HornRaiser. In honor of this final stretch of our 30-day HornRaiser campaign, we wanted to share some reflections from our team about what it is that your donations will be going towards and the impact that this work has on us as social workers. Social work volunteer Lynn Panepinto helps provide an orientation to an asylum-seeking father traveling with his family. How were you able to use your social work skills at the border? Lynn: The ability to remain calm and regulated felt like the most important contribution we could make. Kelly: My social work skills were critical in my ability to manage my own emotions and more effectively support the migrants. The modest knowledge I have of interpersonal neurobiology led me to expect that working closely with people undergoing a traumatic experience could evoke strong emotional reactions and that I’d need to be compassionate with myself. Sarah: At the McAllen bus station, everyone was so appreciative for our most humble offerings of support and empathy. Our contributions felt small, but had undoubtable healing value. Beyond directly applicable clinical skills, this experience also challenged me to reflect on the broader structures and systems that shape the migration experience. I don't have the solutions yet, but our trip compelled me to think deeper about how we can build service and advocacy coalitions, bridge delivery gaps, develop alternatives to detention, and involve social workers in the convoluted and opaque asylum process. Ana: I was regulated and grounded, with the intention that (even for a brief moment) they would feel that way too. I worked to be mindful during my interactions with asylum-seeking families by sitting on the floor and returning control to them. I also involved children into the process by encouraging them to trace the cities that they would pass through in order to complete their journey. What stood out to you about the challenges that asylum-seeking families face? Kelly: It was glaring to me how little government officials would have to do to make a huge difference in a migrant family’s experiences at the border. If groups like Angry Tias and Abuelas and Catholic Charities can fill so much of the gap in needed services, more support from the U.S. government could make things immensely better. The current political climate is oppressive and violent to migrant families in its lack of action just as much as it is in the actions that do take place against them. Sarah: I was surprised by how little information had been shared with migrants about the asylum process itself; what to expect and what their responsibilities are. It was clear that there are no formal structures in detention or immediately post-release to educate families on how to navigate this complex world if they hope to succeed in their legal cases. Many people were even surprised to learn that they needed to seek out a lawyer on their own, and that doing so was the biggest determinant of their case moving forward successfully. Dora: Families are often traveling with young children for several days on Greyhound buses without enough diapers, blankets, cough/medicine, sweaters, etc. and with the extra challenge of navigating their bus itinerary without English language skills. Thankfully, McAllen and the greater South Texas region is a Spanish-speaking dominant area so it makes that process slightly easier. However, that is not the case the further north you travel within the U.S. What is one moment that will stay with you from your experience? Lynn: When we were preparing to leave the McAllen Greyhound bus station after helping to orient migrants there, I was feeling sad because we had run out of snacks to distribute to people for their journeys. Then I noticed a group of volunteers walk in and distribute brown bags of food to people and it gave me a sense of relief and hope, knowing that we are just one piece of the larger puzzle of people who are doing this work and striving to support migrants and their families. Kelly: I remember seeing a little girl who was about 4 or 5 playing with a group of kids at the bus stop with a toy I’d given her a few hours earlier. She was holding it above the small group and saying, “Quién quiere esto?!” (who wants this?!). The other kids replied, “Yo, yo!” (me, me!) They each took turns holding the toy above the other kids. It didn’t occur to me until the next day that they may have been using play to process what they witnessed at the respite center where their parents received donations. Children are incredibly resilient. The Spanish word "Girasol" translates to "sunflower." They were in full bloom during the Girasol team's trip to the border this March. Monica: Walking back over the bridge to the U.S. in minutes, leaving asylum seekers on the other side and passing the line of non-citizens waiting to enter.

Sarah: In the final hour of our time at the McAllen bus station, I took a moment to just pause and absorb the scene in front of me. Mostly families, lots of young children, and the occasional solo migrant. Dispersed throughout, seven fellow social workers, all seated on the tile floor, looking up towards the families on the chairs above them. We usually sat on the ground, both for practical and space reasons, but also to intentionally ground ourselves, ease into the conversation in a gentle way, and chip away at the power differentials that exist between privileged graduate students and vulnerable asylum-seekers. I felt a lot of pride seeing my fellow volunteers in such a visible, symbolic expression of humility and service to others. Dora: It’s always heartbreaking and upsetting to learn about the verbal abuses and humiliation asylum-seekers experience within CBP processing/detention. Often, families are surprised there are volunteers willing to sit and exchange kind words with them. Ana: Witnessing two men who were from the same country reunite at the Respite Center. “You’re here,” one said with overwhelming joy at seeing the other. “I’m here,” said the other. They hugged each other—they both knew how difficult the journey had been and they both knew that it had not ended. No other words were said as they held each other. There was no need. Then, one man said “I see you,” and waved goodbye, and the other man smiled. This interaction was very moving. We thank you for your support, and we look forward to sharing more of our stories after our summer trip. Girasol border trip volunteers Our Girasol team and volunteers took our first trip to the border in December 2018. We trained legal and shelter staff at ProBar, staffed a bus station to ensure migrants knew where they were going, and we helped at the Catholic Charities shelter, which processes more than 300 people who come through the humanitarian respite center each day. Here are some reflections from our team. What’s one phrase or sentence that sums up your experience? Monica: Chaos blanketed with kindness Esmeralda: Resilience personified Ana: Overwhelming need met with overwhelmingly generous support. Chrissy: Witnessing incredible resilience Anayeli: No matter how big or how small anything helps! What surprised/excited/pleased you? Monica: This was my second time visiting the humanitarian center. This is the place where border patrol brings people who are released from their custody. They literally bring buses of people (300-400) a day. We met a volunteer who is a retiree and works there each day. He goes to shake everyone’s hand as they enter the building. He smiles at every person and says hi to every baby. He reminded me of a very basic social work concept in the midst of feeling overwhelmed: relationships heal. Sometimes you just have to smile so people know they are finally safe. Esmeralda: The people who were being served at the humanitarian relief center had been through so much on their travels. It was easy to see they were absolutely exhausted and wanted nothing more than a meal, shower, clean clothes and rest for themselves and their families before having to travel some more, but they always returned a smile and friendly conversation. They were in good spirits and the people who were willing to talk to me showed so much hope and optimism for their future. The women in the clothing room joked and laughed with me and each other while their children played nearby. It was great to see that though they had been through such rough times, they were still able to smile and laugh. Ana: While it was disheartening to see the overall lack of systems and resources to adequately support families crossing the border and seeking asylum, I was incredibly impressed with the networks that have been created by local shelters and the Angry Tias y Abuelas RGV. They work so hard every day to bring supplies, volunteers, and a supportive presence to migrants. I felt that our contribution was meaningful, but it was also good to know that others would take our place once we left and that the migrants we worked with would soon be reunited with family in the United States. Chrissy: What most surprised me was how deep our conversations went with the ProBar shelter staff. While they already knew a great deal about trauma from their work and other presentations, they were incredibly engaged in learning new material, especially when it came to the connection with child development. I think for anyone on the front lines working with asylum-seekers having spaces to talk about your experiences, feelings, and frustrations is VITAL. I enjoyed helping to cultivate that space during our processing groups. Anayeli: I was really surprised that people were not getting any medical screenings before being released from border patrol. I clearly remember a father with his kid who came to us looking for shoes, but his child had a bald patch on his head and when asked what occur the father said he got bit by a spider. Medical volunteers at the Humanitarian Center acted quickly to get this child medication. There is a very real need for medical help. Ana working with a family at the bus station What challenged you? Monica: Control. At the respite center, I wanted order so that everyone got what they needed. I am fine with chaos as long as I control it. Without that control, it is hard to walk away at the end of the day because it feels like there is still so much unmet need. Esmeralda: While the humanitarian center provided so much, there were still many people left wanting. There were not enough jackets, kids’ clothes and stuffed animals to go around, so it was important to assess individual needs and only give certain supplies to people who seemed to need it most. Only some children got stuffed animals because there just were not enough. It was very challenging for me to say no to anyone, but it was necessary. Ana: The most challenging part for me was knowing when to stop for the day. The work at the bus stations and in the shelter is endless. There is always another person to talk to, to orient toward their final destination, to help find some shoes. Knowing how to determine when I had spent my own energy and needed to rest for the day was difficult, particularly in the midst of seeing such high need from both the shelter and the families. I had to trust that other volunteers were on their way and know that this system functions every day without us. All the same, making the call to leave was difficult. Chrissy: What most challenged me was when we ran out of supplies to give at the Respite Center. I found it especially difficult to tell asylum-seekers, many of whom are going to cold destinations on multi-day bus trips, that we ran out of coats. I am from Boston, and imaging the trip there without a jacket was very difficult, especially as many of the asylum-seekers were already sick. Those who run the center every day must strike a very difficult balance between giving everyone what they need, and knowing there won’t be enough for everyone. Those who are able to donate to the Respite Center should know that what they give is very, very, needed. Anayeli: Despite knowing that I am knowledgeable in migrant experiences and feeling comfortable in what I knew, I was there to help and not fix problems. I think as social workers we sometimes have the urge to “fix” things, and with a crisis this big there aren’t many sustainable solutions that could help alleviate the chaos. Anayeli and Ana conducting training for legal and shelter staff at ProBar What unanswered questions do you have?

Monica: Where are the shoelaces? Border patrol takes people’s shoelaces when they are processed at the hielera and people don’t get them back when they leave. Catholic Charities has boxes of shoelaces to give migrants after they are released because they come into the respite center with shoes flopping around their feet. I can’t help but imagine there is a room at the border patrol facility that is filled with shoelaces. Esmeralda: I wondered how much the humanitarian center paid for the shower trailer and if that money might not be better spent fixing the existing toilet and shower facilities inside. I also wondered about the security as far as accepting volunteers. These populations being served are vulnerable and accepting anyone who comes in to help seems dangerous. Ana: How much money would it take to fully and adequately support shelters, such as the one we volunteered with, along the border? I spoke with a man who works at the Catholic Charities shelter and informed us that the building (a former nursing home) had 15 toilets, but that the plumbing needed to be repaired. I wondered – with all of the tens of thousands of dollars pouring into private detention companies, what small percentage would it take to ensure that all migrant families had a decent place to sleep and use the bathroom, as well as the items needed to ensure their comfort (jackets, shoes, sanitary items, etc.) What would it truly take to address the needs of these families fleeing violence and oppression in a humane way? Chrissy: How asylum-seekers get to their destinations. When assisting the asylum-seekers at the bus stop, I was shaken by how little help they sometimes receive to understand the journey ahead of them. Most were taking bus routes that would be difficult for anyone to navigate over several days, with several changes, up to 30+ stops and several hours of waiting in between. For someone who is exhausted, sick, has very few possessions to sustain them, is traveling with children and does not speak English to finally make it to their destination is almost miraculous. My hope is it speaks to the kindness of strangers along the way, and it certainly speaks to the resilience of the asylum-seekers themselves. When they finally see their sponsors, it must be a huge relief. While this system is not perfect, it does also beg the question of why we detain asylum-seekers for long periods of time rather than releasing them to sponsors from Processing Centers, as happened with those we worked with. Anayeli: So at the bus stops we explain to migrants where they are at, to follow up with their immigration appointment, and ask if they need anything on their journey. We noticed children arriving without jackets at the bus station and mothers carrying only 2 diapers to last 3 days. With so few resources and volunteers, I wonder how agencies can better communicate with one another in order to be more efficient in spreading resources. |

|||||||||